Phonological Awareness: What your Brain Doesn’t Want you to Know

Robin Barr, American University TESOL Program

Karen Taylor de Caballero, English Language Training Solutions

Note: This article was originally published in the WATESOL Newsletter (2015) as a follow up to our presentation of the same title.

Presenting at the WATESOL Fall Convention was particularly gratifying this year. With participants saying things like “mind blowing” on their way out the door after our session, we were pretty sure folks enjoyed themselves. We’d like to share highlights from that workshop with you.

The first part of our workshop title, “Phonological Awareness,” may have been off-putting to anyone skimming the program book for interesting presentations to attend, but 24 people were nonetheless compelled to find out what, precisely, their brain doesn’t want them to know.

What doesn’t my brain want me to know?

In short, your brain doesn’t want you to know how you communicate. Specifically, it doesn’t want you to notice all the strange little grunts, puffs, hisses, tones, and other noises that go into conveying a message when you speak.

Why doesn’t my brain want me to know this?

Think of it as a favor your brain does for you. If you had to consciously plan for each sound in each word you were about to utter, you’d have great difficulty thinking about the message you wanted to convey. Take, for example, the phrase: “It’s kind of complicated.” [ətskayndəkámpləkeydəd]

Consider that phrase in terms of voicing: in the course of saying “It’s kind of complicated,” you will alternate between voiced and unvoiced sounds nine times. Now consider that same phrase in terms of phonemes: in just four words consisting of seven syllables, your vocal tract produces no fewer than 19 distinct sounds, each one the result of a unique positioning of jaw, lips and tongue in the environment of the vocal tract.

Now imagine being aware of that… and then take a moment to thank your brain for keeping you in the dark. By being kept in the dark phonologically, you are able to function on a daily basis: ask a question at the store, share a loving thought with a friend, disagree with a colleague, advocate for a child. Your brain gives you the gift of phonological suppression.

Why does this matter?

While phonological suppression is necessary for your own fluent and effective communication, it is not sufficient when placed in the context of teaching someone else how to communicate. As a teacher of language, you need to be able to lift your head above the water of phonological suppression to see—to hear—what is really happening when you speak. In other words, you need to be phonologically aware.

Practically put, your students may be noticing things about your own language that you are not aware of. In teaching, you must be aware of what you’re doing when you speak in order to validate students’ perceptions of your speech.

Validating students’ perception of your own speech is easier said than done. That’s because the acoustics of your spoken English is not the same as what you think you’re modeling. Meanwhile, your students 1) are hearing what is actually coming out of your mouth; and 2) are filtering that through their own language system.

Saying “just repeat after me” is therefore doomed to failure. By itself, listening and repeating is not enough.

Um… can you give an example?

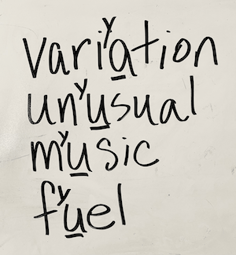

Here is a list of words that our audience recited together at the start of the workshop using only kazoos (to increase our collective awareness of word stress): variation, pronunciation, usual, music, and huge. We’ll return to them later.

Consider the the first of these words, “variation.” Chances are, when you read this word aloud, you sensed a one-to-one correspondence between the written word and its spoken version; you felt like this word was entirely “sound-outable.”

Now ask yourself: How many phonemes (individual sounds) are in the word “variation”?

Participants worked in small groups to answer this question. Answers ranged from four to eight sounds. This range of answers illustrates how effectively our brains hide phonological information from us, itself a revelation.

With some analysis, we were able to observe that “variation” has no fewer than nine distinct phonemes: [ver?yéy??n]

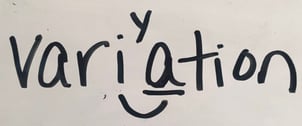

The phoneme hidden from many of us is the /y/ that connects the second and third syllables, noted more visibly like this: variYation. We can refer to this instance of /y/ as an “invisible sound”– a sound not represented in the spelling of the word. (We’re much more familiar with the opposite term: “silent letter”, like the ‘e’ in “have”, or the ‘gh’ in “though.”)

Can you supply more examples of invisible /y/?

Consider this: What is the first sound in “usual”? Most teachers will say “u”, or perhaps “long u,” because they've been told that "a long vowel says its letter name". In Color Vowel® terms, we'd say that “usual” starts with a BLUE sound.

Interestingly, however, we occasionally hear from a teacher asking for an “additional color” to represent the ‘long u’ vowel, because they don’t think the BLUE sound is sufficient.

What would explain this misperception? There are actually two sounds in the first syllable of “usual:” the /u/ of BLUE and something else in front of it. To prove this to yourself, compare the words “fool” and “fuel”. We gave workshop participants minimal pairs like this one and asked them to discover the difference between the two sounds.

The answer? Invisible consonant Y– again!

Throughout the workshop, participants took part in kinesthetic consciousness-raising activities Color Vowel Yoga, “kazoo orchestra” work, and lollipop training, through which they were able to notice exactly what their jaws, lips, and tongues were doing when they made various sounds.

All of this work paid off when, upon returning to our original list of words, everyone suddenly noticed the ‘invisible Y’ popping out:

variYation, unYusual, mYusic, fYuel

Phonological Awareness and Teacher Professionalism

We impressed upon our audience that the English language is filled with phonological surprises that the unaware teacher stumbles into daily and often unwittingly, of which invisible /y/ is only one. To anticipate these surprises, to equip oneself to make informed sense of them, is to be a phonologically aware teacher of English.

Despite the importance of phonological awareness, many language teachers are not themselves phonologically aware (Joshi, Binks, et al. 2009), and this negatively impacts teaching quality (Wright & Bolitho, 1993).

Meanwhile, teaching phonological awareness is crucial for learners of English because the written form of English is often mistaken for a phonetic system when it is not. (The word “read,” for example, can be pronounced as [riyd] or [rɛd] depending on tense.) While English utilizes an alphabetical writing system, one can count neither on each letter to represent a sound, nor on each sound to be represented by a unique letter. This complex relationship between spoken and written English has implications for learning to read fluently (Joshi, Binks, et al., 2009) and speak comprehensibly (Venkatagiri & Levis, 2007).

Conclusions

Steven Pinker (2014) has a great chapter about “The Curse of Knowledge” in his new book in which he explores why academic papers are often horribly written. He writes,

"The main cause of incomprehensible prose is the difficulty of imagining what it’s like for someone else not to know something that you know." - Steven Pinker, The Sense of Style

What Pinker says of bad writing could just as easily be said of bad language teaching. English teachers, especially native speakers, are also victims of this curse: it is very difficult to imagine that our students do not hear the same things that we think we do.

A large part of knowing something is suppressing the irrelevant information – to speakers of the language, anything but the abstract phoneme is usually irrelevant. Our writing system does not include this irrelevant information, and usually we only pay attention to the actual sounds of the language when someone isn’t following our unconscious phonological rules – that is, when they 'have an accent'. But if you don’t know what it is that you do when you speak the language, you cannot accurately identify what others are doing that is different.

It is for this and other reasons that we are committed to promoting phonological awareness as a focus of life-long learning and professional development. We enjoyed providing our workshop participants with a taste of this essential awareness, and we are looking forward to diving deeper into phonological awareness with other “mind blowing” events!

Robin Barr holds a PhD in Linguistics from Harvard and specializes in phonology and psycholinguistics. Robin is Linguist In Residence at American University and teaches in the MA TESOL Program. Robin also tutors low-literacy dyslexic adults at the Washington Literacy Center.

Karen Taylor de Caballero is an educational linguist and teacher trainer. Karen is Director of English Language Training Solutions and is co-author of The Color Vowel® Chart.

References

Joshi, R.M., Binks E. et al. (2009). Why elementary teachers might be inadequately prepared to teach reading. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 2(5), 392-402.

Pinker, S. (2014). The Sense of Style: the Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century. Viking Penguin: New York.

Taylor, K. & Thompson, S. (1999, 2012). The Color Vowel™ Chart: English Language Training Solutions: Santa Fe.

Venkatagiri, H.S. & Levis, J.M. (2007). Phonological awareness and speech comprehensibility: An exploratory study. Language Awareness, 16(4).

Wright, T. & Bolitho, R. (1993). Language awareness: A missing link in language teacher education? ELT Journal, 47(4), 292-304.